Pushes are a (somewhat) complicated

defensive subject. Though being the 2nd (most likely) manor of beginning an assault, Students will often have a difficult time determining

if/when a “push” can be considered to be a aggressive

action (and “legally” justifiable for enacting a defensive

response).

When viewed from a “legal”

perspective, any physical contact (from another individual)

provides a legal justification for a defensive response.

Depending (of course) on how well your able to “justify” that

response to a judge, is open to debate.

Oyata taught that enacting a

(physical) response to a “push”, should be judged (by the

student) through the situation that surrounds the enactment of

that push.

Looking at the physical “act”

itself, it is dependent upon the situation prior to the act

itself. If the “push” is the result of heated verbal

debate and appears (obvious) to the defender, that the

situation will become “physical”, responding to a push

(with a physical response) may be (legally) justified. If the

“push” (only) amounts to someone placing their hand upon one's

chest/shoulder (to gain one's attention), any justification for an

aggressive response diminishes rapidly.

The instructed responses to those

“pushes” (that are considered to be confrontational) are

based upon the legal defense of preventing/responding to an

aggressive (physical) behavior. There are no (or very few)

limitations to defending one's self from being (aggressively)

shoved/pushed. That includes allowing it (the shove) to

occur. Physical contact is not required. Only the act

of attempting to do so is sufficient to respond (to that

attempt).

It is the perceived intent (of

the attempted push) that will dictate the response that is made.

Numerous motions can be utilized to (only) divert the

intended push. Though

preventing the initial action (the push)

it accomplishes nothing

in preventing further/repeated attempts. In those situations that it

is (believed by the student) obvious that

the motion is a precursor

to a (continued) physical confrontation, it is more productive to

attempt to neutralize

the ability for the aggressor to continue any further aggressive

behavior.

Though

not always practical,

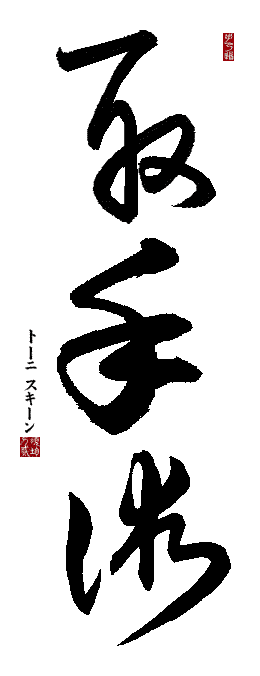

responding with a Tuite application can provide the ability to

neutralize the aggressor (and place them in a position of

submission). As with “Grabs”, responding to pushes

(utilizing “Tuite” to do so) requires extensive practice of the

instructed applications.

A “push” can

be attempted in several manners. The most common (aggressive) push,

is accomplished by (the Uke/aggressor) raising one or both hands to

their own chest (level), with the hand(s) “flat” (palms toward

the intended subject). They (commonly) then step forward (putting

their body-weight into the push) while moving their body forward, and

extending their hand(s).

Whether

the intent is to only rotate a (one) shoulder,

or to knock you onto your ass,

either will cause the student to be placed off-balance

(often as a precursor

to delivering a “punch”). Attempting to absorb

the delivered force (of a Push), is equally problematic

(on numerous levels).

The

manor of (“Tuite”) technique utilized will be dependent upon the

timing of the technique's application. Three possibilities exist, prior

to contact of the push (while the push is motioning towards

the student), following

the act of the push (while the aggressor is retracting

their hand(s), and while the pushing hand is in contact (IE. during the push). Technique's exist

for all 3 situations, and the student should be familiar with each.

All three

situations contain (varying) difficulties in their application. Speed

(in “catching” the hand) when the push is being initiated, and

(sufficient) balance

(after having absorbed

the push), when the aggressor is retracting their hand(s), and the ability to "pin" the hand while the push is being performed.

When

attempting to “catch” an incoming push, there are various

(instructed) methods for slowing

the aggressor's push (including stepping forward, rearward and to the side). Stepping

rearward has the least

likelihood of success (for numerous reasons). Stepping (or

“shifting”) to either side,

is faster/easier and will cause a (slight) unbalancing/hesitation of

the aggressor. Doing so additionally provides opportunity to “grab”

at least one

of the pushing hands. Capturing/pinning the hand to the chest (though probably the easiest) requires a sufficient "grasp" be made (of the aggressor's hand). It additionally limits one's "counter" (attack) choices.

The

practice of the instructed techniques is (commonly) based upon rushing towards

the aggressor, and grabbing

(one of) the intended pushing hands while being raised to the

aggressor's chest (to enact the intended “push”). Being able to do so, of course requires that the Tori was aware of the probability of the action occurring. If/when doing this is

impractical or is (simply) missed,

the instructed method is to (either) capture the pushing hand during it's

retraction (following the completed push), or during the attempted "push".

When attempted as

the hand is being retracted (and if/when the student is physically able to grasp

it), application of the instructed technique is (often) easier

to accomplish. This ability is also dependent upon the Tori having not been initially unbalanced by the performed push.

Regardless of which (timing/method) is utilized, each require sufficient practice with having performed the technique(s). It's true, that even a "sloppily" performed application can often garner (sufficient?) results, but as with any other technique, the more practice one has with the techniques, the better.

Regardless of which (timing/method) is utilized, each require sufficient practice with having performed the technique(s). It's true, that even a "sloppily" performed application can often garner (sufficient?) results, but as with any other technique, the more practice one has with the techniques, the better.

No comments:

Post a Comment