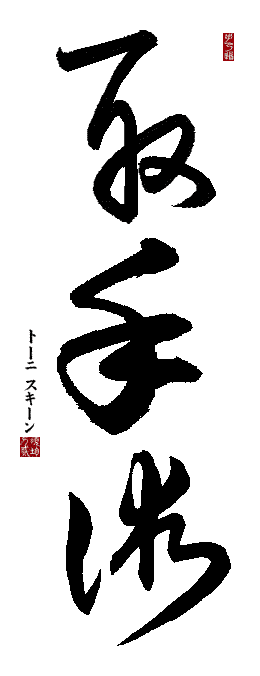

This “Blog” will discuss various techniques (from my own “point of view”), training methodologies, and applications used and taught by myself in the art of “Te”. It will often focus upon the instructed art of “Tuite”, as taught to me by Taika Seiyu Oyata.

Pages

Search This Blog

Wednesday, January 24, 2018

Application of the 6 Principles of Tuite

1. Principle of "X"

2. Primary and Support

3. Fingers & Wrist

4. Positional Paradox

5. 3-Dimensional

6. Force Efficiency

These are the 6 Basic principles that we teach for the application of a Tuite technique. Each is an (individual) factor to be considered for the completion of an effective technique application. It's been interesting (for us) to see how various individuals have been using them (since the release of our book 4 years ago). That book included a number of "basic" technique applications that were intended for readers to experiment with those principles during the application/practice of those technique's (in order to further understand how the principles individually affected each of those techniques).

We have since conducted numerous seminars in regards to the use/application of the 6 Principles, and what we've found is that (the majority of) "student's" focus (only) upon the general technique application (being seemingly content with their level of ability to apply the provided technique's). That's well and good, but the purpose of the book was intended to guide the student in expanding their understanding of how to correct the provided technique's if/when they either perform them incorrectly and/or the Uke provides some level of "countering" action that's intended to prevent the technique's application.

The majority of those "counters" are based upon some level of misapplication (of the original technique) being done by the tori (and/or a completely unrealistic situation). Many of the (supposed) "fixes" (by other's) for those situations are based upon the inclusion of "strikes" or some degree of muscling a technique (in order to "make" it work).

The premise of using a Tuite technique is to avoid the use of impactive applications ("Strikes"). That premise is

base on the circumstances of the (individual) situation. Not every confrontation will allow for the use of a Tuite technique application. The (practical) use of a Tuite application is circumstantial and is subject to the individual's ability to create and/or take advantage of those situations that make those applications practical to utilize. That practicality is determined by the level of the user's ability (with those applications). Every Tuite technique requires the Uke to (initially) perform a specific action (commonly some level/degree of a grab).

The purpose of an (any) "grab" is either to immobilize (a limb, or the Tori in general) and/or to allow the Uke to then strike with their "free" arm. Although (additionally) often used as an attempt to unbalance the Tori, any included attempt to strike (with their free arm) is subsequently minimized. The correct use/application of the instructed Tuite technique's can negate either of those attempted actions.

When we provide a seminar that covers the 6 Basic Principles, we commonly spend an hour for each of those principles (in regards to their explanation). Although they can (obviously) be "listed" in under a minute, their (detailed) explanation can entail a far greater amount of time (for the student's to understand all the relevant circumstances of their application). Though we feel that we provided a decent level of explanation in the book, reader's (and student's) should recognize that there are (numerous) details that can be expanded upon (beyond what was done within our book). Our (original) beliefs were that readers would research those factors (on their own) and we would subsequently be presented with questions in regards to that research (that belief has rarely come to fruition).

We've been approached (numerous times) in regards to the "2nd" book, but we've found few (if any) "examples" of sufficient understanding for the initial "6" to justify that release. The majority of what is illustrated in our 2nd Tuite book, are corrections to misapplications of previously illustrated techniques. It includes numerous correctional applications (for commonly performed mistakes made with the originally shown technique's).

Although numerous instructor's show these types of technique's as "new/different" applications, we teach them as corrections (to incorrectly performed technique's). It shouldn't be the learning of "new" technique's, but the correction of already practiced techniques.

What we've observed (done by other instructor's/system's) is the instruction of those (or similar additional?) "principles" as being necessary to a technique's application. This is (both) inaccurate, and disingenuous. Those factors can include: Distraction, (Technique) Reversal, Compression/Expansion, and Redirection. These factors can prove useful when one experiences difficulty with a technique's application, but they are not "necessary" for a technique to (typically) be utilized. They additionally require that the student understand how a technique should (initially) be practiced. They are utilized as situational corrections to the misapplication of the originally attempted technique.

We've observed numerous (instructor's?) people emphasize these factor's (in one form or another) as being necessary to a technique's application. This is only accurate when the technique is being incorrectly practiced to begin with. To be fair, many of the individual's were taught those technique's incorrect to begin with (regardless of where they claim to have learned them).

If/When any of the technique's that we teach (or illustrate within our book) require that you "muscle" it (use excessive physical effort to elicit a correct reaction to the application), you are performing the technique incorrectly.

Although instructor's (in general) love to emphasize that everything taught (within a system) is interconnected, each of the instructed pieces require separate/individual practice (to create that relationship). Student's will commonly have trouble (?) with individual techniques. It is those technique's that the student should focus their practice upon. This will commonly include understanding exactly what is/isn't being achieved (in the student's performance of those technique's) to make the application successful. It is this (type of) research that will constitute the majority of the student's practice and study.

Our provided 6 Principles are intended to aid the student in that research. When a student encounter's a "problem" with the application of a particular technique/application, the student should research the application of each of the 6 principles (within the chosen technique) to see where the misapplication exists.

Student's will commonly misapply a single (or multiple) aspects of the particular application. The 6 Principles are intended to be used as a "checklist" (for determining where/how the misapplication is being made). This commonly requires a greater understanding of those principles than is being made.

Those mistakes are often (very) "subtle", and once having been pointed out, the student can/will readily correct the misapplication. This is (very) often what our Tuite seminars encompass, the "pointing out" of subtle mistakes that are performed by the attendees/students. It isn't that those students are "stupid" or even unknowledgeable (in regard to the practiced motions). They simply haven't recognized their own misapplication of the technique's to the degree that we are presenting them (to those students and/or within our book).

Regardless of which "style" of defensive art one practices, the application of these techniques will (should) be done similarly. As we move forward in our own practice of the instructed techniques, we have ceased to be as "Style" orientated. The subtle differences that do exist between the various systems more often amount to "triviality's" that bear no relevance to the instructed applications (I.E. "Tuite"). Oyata taught that all Okinawan "styles" were (essentially) the same. Each was influenced by an individual instructor (who emphasized what they believed to be most relevant to their system), but the common instructional "goal" was the same. Our book(s) and seminars are orientated likewise.

Labels:

atemi,

brush calligraphy,

jujutsu,

jutsu,

Kansas City Missouri,

karate,

kempo,

Kyusho,

Life Protection art,

Oyata,

ryukyu,

Ryute,

Seminars,

shodo,

Taika Seiyu Oyata,

te,

techniques,

Tuite,

Tuite book/DVD Schedule

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)