“Strikes are the primary weapon for defense. But if that defense is breached, we practice trips, sweeps, throws, and takedowns; and “then” basic grappling techniques.”

I read this recently in a blog, where the individual was lamenting over how martial arts had changed through the years since he had begun studying (some 20 to 30 years ago). I read this, and agreed with his (basic) premise, but feel that this order (of priorities) was wrong then, and it is wrong now.

One could argue that in times past, society was more prone to violent confrontations, but I don't believe that to be an accurate summation. Violent (physical) behavior has never been a socially accepted method of settling disagreements. A person recognized as an asshole 2-300 years ago, is no different than their modern day equivalent.

Misogyny was more prevalent (in the past), but that didn't mean that physical altercations were any more socially acceptable than they are today (the “laws” in that regard that were in place then, were very similar to those in place today).

The subliminal implication being made (within that statement), is that “might (tends to) make right”. The (obvious) refute to that statement, is that any laws that a society has put in place discourage and have punished individual's who have participated in anti-social behavior (IE. Physical altercations). If it were (at all) accurate, then only bullies and brutes would be the individual's dictating the standards for social behavior.

The (age old) argument, is that “criminals” don't follow laws (which is true). The problem is that you are rarely going to be involved in an altercation with a criminal. The majority of physical altercations are between two (basically) “law-abiding” persons, who (for whatever stupid excuse) get into a dispute that turns physical. Those altercations commonly have no intention of ending the life of (either of) the participants, but amount to establishing the “correctness/validity” of the participants' view (over the subject being disputed).

When pressed, most individual's recognize this fact. In today's society, being involved in a physical confrontation will commonly result in “legal” repercussions being included as well. The majority of the articles I have read tend to ignore this fact as well. They (somehow) believe that if they are “justified” (in their mind), then the law will be on their side. These people have never been involved in a legal battle where the “bad guy”, has a good lawyer. It is VERY easy for that lawyer to argue (to the judge) that you escalated the situation far beyond any reasonable level (for the situation). The mere fact that you train (in a martial art) will be used against you, and will be believed that you have violent inclinations, and used this “opportunity” to test them out (on their client).

Don't believe that you're going to even see, a jury. Your far more likely to be in front of a judge, with the person's lawyer describing everything (whether accurately, or not). The other party will rarely make any statements at all (the lawyer will present the majority, if not all arguments). And yes, people LIE all the time at these proceedings (including witnesses). If you don't have a superior number of (believable) witnesses for your side (and even that isn't a guarantee), you will lose.

In regards to the “order/priority” of those training subjects, the one provided by that individual was (IMO) completely backward. The “first” subject learned (when training), should be those “basic grappling technique's”, followed by the “trips, sweeps, throws, and takedowns” and completed with instruction in the systems methodology for the use of strikes/kicks.

Experience has shown (myself) that confrontations proceed on the basis of performed responses. If the confrontation remains verbal, there is less chance for a (physical) requirement/necessity to respond. As proximity is diminished, that need/belief escalates. “Pushes, grabs and shoves” are (commonly) used as taunts to motivate the individual to (physically) react/respond. Though (obviously) not intending to injure (but more to embarrass), that physical contact is (none the less) illegal (often providing the legal justification for a defensive response). Although being justified, that justification does not provide for an unlimited level/amount of response (meaning you can't dislocate someone's arm, crush their throat, and gouge out an eye, because someone pushed you).

Any level of response that you enact, will need to be seen as reasonable by the average individual. If/when there is a physical disparity between the (original) aggressor and the student (defender), they will have a greater chance of their defense being seen as a reasonable/expected reaction.

One's competence with the Tuite technique's will provide a defensive method that (when observed by any witnesses) provides a less violent appearance to the student's defensive motions. Its use (Tuite) can additionally discourage (though obviously not always prevent) the inclination to escalate the confrontation to more violent/physical levels.

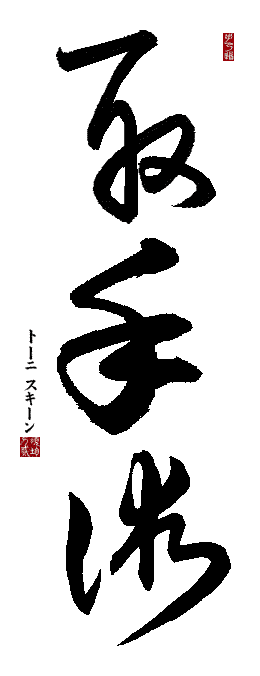

The most popular argument regarding the use of Tuite is the (mistaken) belief that it doesn't work on/for “everybody”. I (personally) despise the words “always/never”, but as yet, we have not encountered an individual whom these applications have/will not “work” upon. It should be noted, that “Tuite” is not universal. Prior to “Oyata's” introducing it (here in the U.S.) I know that “I” had never seen/heard of it (and I had been practicing/teaching M.A. For a number of years before meeting Oyata). We only practiced some “Jujutsu/Aikido” types of “wrist/arm” manipulations. Nowadays, everybody teaches their own form of grappling/wrist applications, and have begun to (now) use the term “Tuite”.

Once those “grappling” applications are understood, the “Trips, throws and takedowns” are (much) more easily utilized. Either of these application methods (Tuite or the throws/takedowns) lead directly to the restraint/submission of an aggressor (with little to no need for “strikes” to be utilized).

Does this imply that I/we don't believe in striking? of course not. It simply isn't our primary defensive choice. The success of a Striking technique is subject to numerous factors that a student has limited (if any) control of. Striking focuses on many students basic instincts (unless that student is female and/or a smaller stature male). Those that believe the shown “grappling” techniques are dependent upon having (enough) “strength/size” (for their use upon an opponent), don't understand the technique's (to begin with).

Striking techniques will vary in their effectiveness, because of circumstances that are often beyond the control of the student. If that student is only (attempting to) focusing their attention on (including) physical “power” with their strikes, they will only achieve limited levels of success. Power equates to the transferred momentum of a given mass. That transfer is accomplished thru speed, leverage, and (sufficient) penetration. Equally relevant is the impacted location, and the angle of that impact. This shouldn't (necessarily) be equated to the use of kyusho (study/instruction), only logic.

If/when an impact is perceived (by the recipient) as being direct/straight, the manner they react will be different if/when that impact is other than their initial belief/perception. This is similar to if/when one “twists” their ankle, they perceived a different tread point/location (than what actually existed), and the subject trips/stumbles (injuring their own ankle). An aggressor's perceptions can be manipulated with proper training (this was one of Oyata's most popular subjects for instruction).

Through arrangement in this order, a student is provided with (more) applicable technique's earlier in their study.