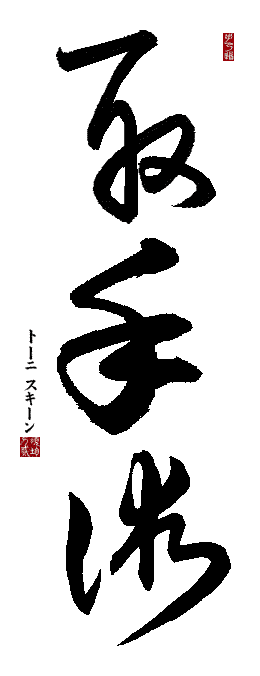

I

am often asked why I practice Oriental brush calligraphy. It

(seemingly) has little to do with the Life Protection methods that I

study and teach. First, I just happen to enjoy it, second, it is

composed of a number of intricacies that are very similar to the defensive methodology that I practice (that of Seiyu Oyata). I additionally liken it to the practice of kata

(of which there are numerous similarities).

When

our students are shown the beginning kata motions, they are provided

with the general motions. As the student defines those motions

they are guided in their own individual refinements for performing

those motions (as was taught to us by Taika Oyata).

The same is true

for my brush calligraphy student's study and practice. They are

initially shown the general motions (strokes) and those strokes are

refined until they are performed in the manor recognized as being

“correct". As with the kata, those individual motions will be

performed by the student (through numerous individual aspects) in

their own manner, yet will adhere to the instructed methodology (in

our students case, those methodology's will consist of Oyata's (Life

Protection Methods), and the Japanese Calligraphy Assoc. {Nihon

Shuji) for the brush calligraphy being shown.

In

either subject, the motions could be performed by “other”

students (of different methodology's) in various (different) manners.

That's not to say one is (necessarily) better than another,

only that there will be differences. Those differences really amount

to differences of purpose. The purpose of Oyata's methodology

is efficiency in the practice of Life Protection applications, the

purpose of the Nihon Shuji methodology is beauty (granted, a relative term) in

the creation of Oriental Brush Calligraphy. These are two seemingly

different pursuits, but they share numerous commonality's in their

study and practice.

When

practicing the instructed kata motions, the student is attempting to

reproduce the motions in the manner taught, while maintaining correct

stature and breathing (during those motions). The same is true for

brush calligraphy. When any of those subjects are neglected, the

entire process suffers (or is performed incorrectly).

This

is how (or why) observing a (possible) “opponent”

performing kata could deter one from engaging in a confrontation with that person. When

an experienced shodoka views a piece of calligraphy, they

(likewise) can “see” the skill level of that person's

calligraphy.

In

either subject (kata performance or brush calligraphy), the experienced

practitioner should be able to see the level of the

performer's abilities (in that subject). Students (of either subject)

who only strive to “reproduce” those motions, are readily seen to

be “beginners”. Those that can “perform” the actions

(fluidly), and without conscious effort, are seen as

knowledgeable (if not skilled) in/of the subject.

Kata

motion represents more than just the “obvious” motion(s) being

performed. Interpreting those motions is known as “bunkai”.

Deciphering the (numerous) interpretations for those motions,

involves serious study for the applicable interpretation of them.

The

majority of whats commonly being presented (as being bunkai)

is IMO, more often simplistic “battering” applications. Though

(possibly) valid, they are more often only applicable via (physical)

size, force and strength. None of which are elements of/for advanced

study or application. Motion and positioning are the more relevant

factors to the applicable bunkai.

One

may ask what the connection to brush calligraphy is? It must first be

understood that the Tensho (style) is the oldest style of

Oriental (brush) writing. These were based upon pictographs. They

were then modified via various changes to create the other (common)

styles of brush calligraphy (Sosho, Gyosho, Reisho, Kaisho,

etc.). Tensho is (kind of) the “bunkai” of the present day

Kaisho (style). Without understanding how calligraphy transitioned

through the various “style” changes, it would be difficult to

understand what the original “Tensho” (style) consisted of (for

the character).

When

attempting to interpret kata motion, the most difficult part (IMO),

is determining where to begin, and where to end? (for

the relevant motions). Even when those motions are decided upon, a

“full/complete” technique/application may require additional

motions (and often from multiple kata).

Many

people (when trying to decipher kata motions) attempt to make the

motions fit (often) bizarre situations (IMO), or represent

motions that they already know (believing that bunkai is only

simplistic representations of equally simplistic defensive motions).

This doesn't make sense? (for a technique/system mnemonic).

Much less for what are generally considered to be “secret”

techniques of/for a defensive system that someone wants to

remain secret.

I

believe the motions are (more so) representative of commonly utilized

(if not general) defensive motions that can be utilized in various

ways, and in commonly encountered defensive situations. This implies

the motions are more akin to application “principles” (as opposed

to specific techniques). That doesn't make the interpretations

simplistic, just not readily recognized (hence the need for

“research”).

This

is why we spend (a lot of) time with researching individual

kata motions. Using the examples provided to us by Oyata, has given

us numerous directions, methods and means to apply those concepts to

kata motion (for both defensive actions and the application of

Tuite). For myself, Shuji is a constant reminder of those concepts and origins.