After 30-some years of teaching experience, I've found that students are inclined to obsess over Pain (either receiving it, avoiding it or creating it). For many (initially), they may be trying to learn to avoid it (at least occurring upon themselves). As they progress in their studies though that perspective is ..redirected.

As students progress in their study, they learn to seek a desired reaction in order to understand their own (proper) positioning for the application of that technique. Not that you should be desiring to (specifically) inflict pain, only that you seek to recognize the position and/or limits that create a practical “reaction” to the applied technique.

With that understanding, you can choose (while applying a technique in a defensive situation) whether only soliciting pain is sufficient, or if damage is required to neutralize the aggressor (as well as how to avoid it yourself, if/when a similar technique is attempted upon you).

Pain is usually measured by the level of reaction (motion) away from the application. The student needs to be familiar with the limb's R.O.M. (Range of Motion) so they can precipitate those reactive motions as they occur (or don't occur if/when the technique is improperly applied).

Understanding R.O.M. Will aid the student in responding to unexpected reactions as well (example: if you stomp on someone's foot, they will tend to strike or push you away prior to tending to their foot). This is often done with no conscious (or even necessarily malicious) thought, it's a simple reflex response.

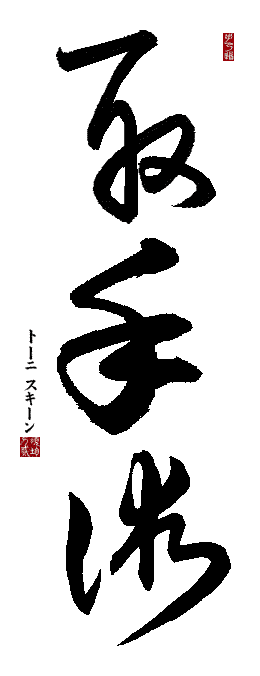

Though pain can be a useful reference in a classroom environment, in an actual encounter, the adrenaline surge that is usually experienced (by both parties) and can distort, or even negate any perceived pain levels. It's for that reason that a thorough knowledge of R.O.M. Needs to be understood. The knowledge to mechanically limit/restrict the ability of another to move, is an often overlooked aspect of limb manipulation (Tuite).

The commonly misunderstood aspect of Tuite, is that although those techniques are often painful, pain is not the reason they work. Just as there are subliminal nerves that make your heart pump, there are nerves that oversee the well-being of the body. When those nerves detect an undue, or potentially damaging situation about to occur (whether real, or only perceived as being so), they create responses (commonly through body-motion) to avoid that occurrence.

When a Tuite technique is applied upon your wrist, why do the knee's buckle? The body is taking care of itself whether any pain is felt or not (and motions the body in order to relieve that pain/perceived threat). Oyata's techniques, and the reactions elicited through their use, are based upon the body's natural motions and their responses.

We tend to view pain as a bonus. If it occurs great! (our job will be easier), if not, doesn't matter, the body is being mechanically manipulated (which will negate the subject's ability to physically resist and/or retaliate).

Typically, people associate Kyusho with pain as well. This is a similar scenario. Though Kyusho points are often painful, that pain, is not (always) the desired reaction. There are numerous Kyusho locations that elicit NO pain what-so-ever (when utilized).

Many of those locations are unrecognized mechanical leverage locations as well. I find it amusing to have student's ask about the locations of Kyusho points. They often expect them to be some not previously recognized location. Most locations are (in fact) realized, it's just not known how they should be utilized.

In either case (Tuite or Kyusho), it isn't always the pain that is the (sole) motivator, or immobilizer. It's the mechanical inability to counter the technique and the recipient's inability to prevent the response or reaction, that makes the technique valuable to know (as a defensive tool/response).

No comments:

Post a Comment