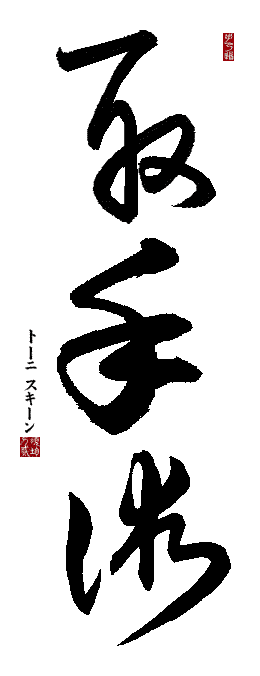

Oyata's

methodology (regardless of the time-period

for that instruction) has always emphasized (entire) "body"

motion/use during the application of the instructed motions. That

instruction varied/changed over the course of his (years of)

instruction. This came about because Oyata was constantly striving to

improve the instruction that he provided to us (his students). Many

of the concepts that he taught, were provided with no definitive

"labels" that distinguished those principles. Many of them

encompassed several (sub) subjects. One of the major ones, we have

"labeled" as Force

Efficiency.

Force

Efficiency is the term that we use in our instruction of the

(physical) application of the instructed motions utilized within the

Oyata Te system. Oyata did not use this term, it is the phrase that

we

coined to define the manner that he (Oyata) taught and utilized to

convey that concept. The term is used to define the efficient use of

the physical actions that are taught to our students (via the

instruction that was received from Oyata). Our use of the word

“Force” should not be confused with Forceful

or to imply “strength” (within the use of those applications).

The

average student is initially inclined to believe that having a

greater amount of (physical) “strength” will assure that students

use of the instructed motions will (always) prove to be the most

effective (if not efficient). Of the (multiple) factors that

determine the “effectiveness” of an application's use, the amount

of applied “power/force” is considered to be the least

important (the correct “placement” of that application being

significantly more important).

When

one is determining what factors are the most universally available,

physical strength

is only one of, if not the lowest/least important on that list. If/when a

technique isdependent

upon that “one” factor (I.E. “power”), it is (then) only

applicable by a limited number of individual's (male or female). That

use is additionally dependent upon it being greater than the

opponent's ability to resist/absorb that application.

The

student's knowledge of an opponent's natural "weak spots"

(not necessarily "Pressure Points") is necessary for the

use of those applications. That awareness/knowledge is taught through

the instruction of the student's use >of

their own body (within the instructed motions).

Force

Efficiency is the initially instructed "awareness" of those

strengths (and vulnerability's). Though (initially) taught as an

efficient means of technique delivery/use (by the student), it

additionally exemplify's an opponent's vulnerabilities. If/when

involved in a physical conflict with an opponent who is

larger/stronger, the student must have the ability/knowledge that

allows them to circumvent those advantages. This awareness is

exampled in every aspect of the instructed positions/motions.

When

people (generally) speak of Oyata's technique application, they

(commonly) will refer (if not “obsess”) to his use of a

“neck-strike/knockout”. This technique (though being very

impressive) was often difficult (if not "impractical") to utilize in a (more "common") altercation. If that

technique were as "effective/practical" (as people

generally imply)

why didn't Oyata spend more

(if not the majority)

of his classes being devoted to his student's perfecting it?

(obviously) Because it wasn't

(either “easy” nor practical

).

Depending on the circumstances, it more often resulted in a “stun”

(or temporary imbalance

of an opponent (thus becoming a glorified

“atemi” strike, which was what Oyata

considered it to be.

Our

use of the term "Force Efficiency" is used to exemplify the

student's most efficient use of their body and appendage motion in

the application/use of the instructed positions, motions and

techniques (whether defensively or offensively). That instruction

begins with the student learning/understanding what motions are

natural

and what motions are not. That includes the subliminal

motions that occur in response to expected and/or unexpected actions

(performed by the student or Uke during an altercation). The

student's awareness of those responses allows them (those responses)

to be utilized within the student's application of (the instructed)

technique. <

When

one examines what constitutes “natural” motion, it commonly

consists of forward

motion (by the bodies limbs.

Those motions that are “circular” (or rearward)

are not considered to be as “practical/effective” for use (as

those that are delivered

directly

forward). (in general) Circular

motions require “room” to develop momentum.

It is also difficult to (efficiently) include the user's body-weight

with those types of strikes.

Oyata

Te demonstrates the positioning of the student's hip's and shoulders

during those application movements. In general, the hip's and the

shoulder's remain (consistently) "square" (to one another)

during any motion/movement. When that alignment is altered, the

student will be (and "feel") off-balance.

I have recently seen (several) “examples” of individual's

performing (their own)

versions of Oyata's method for performing the Kata (the versions that

he taught). What's commonly exampled, is a quickly

performed example, that includes (numerous) incorrectly

“added” motions (as well as motions that were removed

by him as well). Oyata did

include additional motions, but they were intended to be (very)

subtle (and barely recognized/noticed).

One

of the most obvious (of Oyata's changes),

was the elimination

of (any) "shoulder-wag" (during the performance of the

kata). The reasons for doing so are multiple, but its inclusion

is an obvious indication of not having been part of his later (I.E.

the last 10-15 years of his life's) instruction. The examples I've

seen may have been (at one time) "valid", but they should

be (more accurately) considered as being "basic" (and

certainly not "advanced", as those posters have claimed).

Oyata's

later years of instruction focused on the student's use/positioning

of their body (whether during technique or kata) motion. He felt that

this was of higher/greater importance than (individual) “technique”

use or variance. Those motions held greater importance than the

learning of different or additional technique motions. Once those

motions were understood by the student, techniques would become more

obvious

(via the kata motion) to the student.

I've

received numerous inquiries as to why I don't post "video's"

of new/different technique applications. If my readers refer to our

Oyata Te page, my associate has included (numerous) videos that

example (much) of what I have addressed here (technique

motion/application, etc.). Frankly, "feeding" the

Internet's "need " video examples is not my goal (here).

Those

that (actually) are

interested in what/how we teach Oyata's methodology should

visit/attend our classes to get a more descriptive (and physical)

“exampling” for what/how we teach his methodology. Our Classes

are (very) relaxed and we are very

open to explaining the “how” and “why” of Taika's teachings

(as well as those teachings that he didn't

agree with).